September 1993

Lungfish may be one of Baltimore’s most successful bands. With three albums on Dischord, they tour and sell records world wide. Yet their success is little heralded locally.

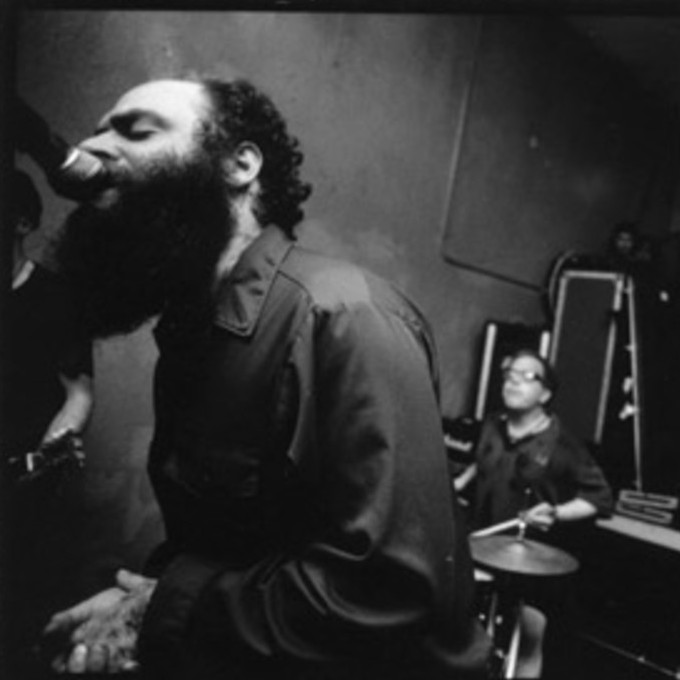

Mitchell Feldstein is the drummer. John Chriest plays bass. Daniel Higgs is lead singer. Asa Osbourne is the guitarist.

Here’s their story, in their own words...

On The Origins of Lungfish:

John Chriest: Daniel was in one of the last incarnations of the Baltimore band Reptile House. Asa was in Reptile House also. They only did three or four shows and the group exploded.

So that’s how Daniel and Asa knew one another. Asa and Mitchell were both in a band called Per Capita. When Per Capita was happening I was in a band called The Melvin and we played the Dulaney Inn together.

Between Reptile House and Lungfish, Daniel was firmly ensconced in the Apathy Press poets with Tony DiVinti, doing poetry readings.

Daniel Higgs: I had known Tommy since I was 18 or so. I’ve been writing since I was a kid off and on. I started reading it really young. I read like Yates, some Dylan Thomas. Tom was watching over what I was writing here and there. He was publishing his own books and asked me if I wanted to do one and I said sure. It was Under Heaven’s Heel.

John Chriest: I’d been going to some of the poetry readings at Maryland Institute, Cultured Pearl, The Jar. I’d been talking with Daniel and we started doing sound collages and sound effects, tape loops to his poetry.

Daniel Higgs: For the first six or eight months we didn’t have any particular goals. We worked a lot of Dick Tuner, inventor of the Smile Machine. He would work with these tone generators and tape loops and things like that. Eric Meyers came and played Electric Scissors and an electrified metal door. It was just trying to make our own fun, basically. We played at Harvest Moon Vegetarian Restaurant, the Maryland Institute, the Hour Haus.

John Chriest: We weren’t interested in starting a band. We were just interested in playing some songs in a band situation. So we called up Asa and Mitchell and it just seemed to grow on its own. This was about 1988.

On Signing With Dischord:

Mitchell Feldstein: Dan left for San Francisco right after we recorded the first album. At that point we thought we would document what we had done. Somehow we got hooked into the [Washington] D.C. scene, and a new label in D.C., Simple Machines, liked our tape and wanted to put it out. They needed some backing so they hooked up with Dischord to put out the record as a split release.

We were getting interesting feedback so we figured, ‘Well lets try to go on a tour.’ We went on a six week tour across the United States and when we got back Dischord wanted us to record again. We've been together since.

On Recording:

Daniel Higgs: Recording is a strange thing to do. It seems real cut and dry, like you're going to go and and play the song the best that you can and Boom! you're done. But when you get in there, it is a lot more nebulous than that When you you record a sound and then play it back, you are not sure if it's the sound you are after and then then it makes you doubt which sound you're even after in the first place. It all can be confusing.

It's like when you're talking. You have an idea and you want to say the idea but once you say it, the words you use to explain the idea become the idea and you can have a real hard time getting back to the original idea before you uttered it.

Mitchell Feldstein: We recorded all three of our albums in six days. If more bands did that they would have less stress when they made their first record. They obsess on getting everything perfect rather than being as good a band live as they can be.

On Working With Ian MacKaye (producer for the new album):

John Chriest: Ian Mackaye is a strong person. The engineer, Don Zientara, is a real strong person to work with. They’re both sure, not cock-sure, but sure. So it’s easy to communicate and run through ideas without getting fixed on any one, to keep the whole picture and settle down on detail work.

Don worked with Ian a lot. Don knows what machines Ian likes to work with, gives him the variables. Ian doesn’t like to play around with a lot of stuff except after he gets an idea. He doesn’t just like to noodle with the equipment He’ll get inspired and know what he wants.

In the production, we’re all there. It seems the best way in the studio, you’ve got to let the person mixing mix. Everyone’s excited but we try to stay in the background until he gets something worked out. And then he’ll look around in his chair and say, ‘What do you think?’ And each one of us will have a take on it.

Ian’s seen Lungfish a number of times. He knows what we sound like. We try some ideas out and he would just go with it.

On The Lungfish Sound:

John Chriest: I've heard a lot of things that sound composed, but were made up on the spot. Jazz in the early ''50s—Miles Davis, John Coltrane—they'll all be listening to each other so much that they'd play off one another and make it up as they go along. And it's not a bunch of slop. It sounds composed. But it's more immediate, more fresh, more emotionally sound.

We have deference to one another in the band. It's not like a bunch of people soloing. There is a lot of listening. I found there's layers of listening as a musician. You can approach things on the surface but then you go deeper, play of the other person's emotions.

When we come into the room we pay attention to everybody else, as well as ourselves, and start to put the songs together. If it feels good to me and if it makes sense then that's the way it goes. If you're not comfortable with what you are playing, you shift what you are playing until you can be. Sometimes Daniel's words will be great and we’ll have a song but it’s it is not getting it for him, maybe he’ll come up with different words. We all do that. We shape it together on our own until we come up with something we’re all happy with.

The way I feel, I can write 60 million bass lines, and I can play the same bass line any number of different ways. I’m not so fixed on it. Practice after practice we work through a song, play it three times and start another one. When you have so many songs you don’t have any of the tension of ‘This song is a great song and I love it and it has to be this way or I’m quitting.’ In many ways, that’s creative immaturity.

On The Lungfish Words:

Daniel Higgs: When you’re saying poetry aloud without music, there’s no constraints verbal-wise. But if you’re playing with music, if you want words to be with the music and not work against it. The melody and the rhythm are going to edit the words for you. Some words are just too much of a mouthful or too awkward. The music doesn’t shape the sentiments but it definitely shapes the sounds of the words.

I’m not really too conscious of verbal theatrics. There’s not usually a punchline in our songs where there’s one word or one phrase that’s going to be emphasized because it’s more important. Our songs tend to be not so many peaks and valleys, they’re more straight across. We’re not especially conscious of arranging songs so they’re especially dynamic. We play what we think will sound good. It’s not like we’re trying to milk or manipulate an emotional response for who we presume might be listening.

On Reconciling Rock ‘n’ Roll With Adulthood:

John Chriest: I work in a health food store; at the Golden Temple. I like that environment. It keeps me in the real world.

Mitchell Feldstein: I’m a licensed social worker. Asa moves art and Daniel is a tattoo artist.

Daniel Higgs: I don’t think the music we’re playing has to be youth centered. I grew up with rock and roll and I imagine there’s going to be some rock and roll artists I’m going to be listening to for the rest of my life. I’m not going to hit 30 or 40 and sell off all my rock and roll records.

When I was 25, 1 went through that whole thing ‘Man, I’m too old to do this’ and (a friend) explained ‘No one ever told Muddy Waters he was too old.’

It’s just youth culture. It’s just the way industrial capitalism holds people to certain paths. People who are 22 are so uptight because they’re not making $40,000 a year. Rock ‘n’ roll is not rebellion anymore. It’s not that singular.

--Joab Jackson, ROX magazine