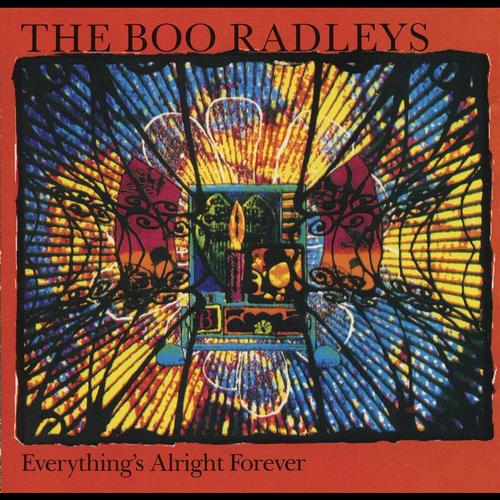

The Boo Radleys' new album,

Everything's Alright Forever is pop's difficult spectre. Not

one song falls into pat sentimentality, pat anger, pat love or pat

anything. Rather it mars the environment with its blunt presence,

like ugly furniture. Only when you pay close attention does

Everything's subtle charms appear.

The Boo Radleys' new album,

Everything's Alright Forever is pop's difficult spectre. Not

one song falls into pat sentimentality, pat anger, pat love or pat

anything. Rather it mars the environment with its blunt presence,

like ugly furniture. Only when you pay close attention does

Everything's subtle charms appear.

Everything's Alright is simultaneously distant, with eerie guitars far off in the mix, and all too immediate. “Room at the Top” tumbles with boulders of white noise (you fear for lead singer's Sice's fragile voice). Mind you, this isn't My Bloody Valentine's type of noise, all tempered and tapered. This is the stuff you hear when you can't quite tune in your favorite radio station. Mountains of the stuff.

Little wonder the Boo Radleys unnerved their producer, Ed Buller. While making the album, the arguments were frequent, according to songwriter Martin Carr.

“A lot of producers are nervous about doing things differently, things that they think or other producers think are wrong. Which is pretty sad, really,” Carr says.

White noise is inseparable from the Radleys, though.

“It's something that's fascinated me since Jesus & The Mary Chain used it seven years ago. Not anyone can do it. When it's used wrongly, it sounds really dull. But some people can make it sound really fresh,” Carr says.

Not that noise is solely what the band is about. Arguably the best song on the album, “Spaniard,” sounds like a pop condensation of Miles Davis' Siesta album. A forlorn trumpet sings in the distance, only to be overtaken by thick, successive layers of sampled harmony.

The Boo Radleys started young. The members grew up in run-down Liverpool.

“Me and Sice [Simon Rowbottom to his mum], we've known each other since we were 10. When we decided we were going to form a band, we just talked about it and practiced interviews for 10 years, and then we decided we would have to learn to play an instrument before we could do it.”

“So we did that, and we met Tim Brown, the bass player in school, but it wasn't until after school that we actually started doing anything,” Carr says.

At the time the Radleys were pulling together as a band, the British music scene was undergoing convolutions. New bands like My Bloody Valentine, A.R. Kane and the Cocteau Twins were redefining the use of voice, guitar and feedback in rock, producing oceanic washes of sound.

“When we started, we were a cross between Valentine and Dinosaur Jr.,” Carr says. In 1990, they released a mini-album Ichabod & I (Good luck snagging a copy—it's available only on the tiny British label Action). Soon after, they were signed by Rough Trade, a blessing that soon turned hindrance.

“They couldn't afford to pay for us to do an LP,” Carr states. Instead, the Radleys released a series of EPs in the U.K. Kaleidoscope (1990), Every Heaven (1991) and Boo-Up (1991) all recouped Rough Trade's investment and then some.

In the spring of 1991, the band was finally given the go-ahead for an album. They recorded Everything's Alright Forever. Unfortunately by then, according to Carr, the financially struggling Rough Trade “couldn't afford to put it out,” Carr says.

The band was stuck. While bands like Lush were making their name known in the U.S. with similar sounds, the Boo Radleys were rendered silent. Moreover, MBV and A.R. Kane's influence started to filter down to second-generation bands.

“It just got a bit silly. There's a million of them, none of them are any good: Slowdive, Ride—terrible bands,” Carr comments.

Only when Rough Trade went belly-up was the album picked up, by the Creation label. Now the band can stand alongside their contemporaries.

So when the Radleys tour the U.S. this fall, how will they answer the inevitable MBV comparisons?

“Kevin Shields [My Bloody Valentine's guitarist] is more concerned with getting far-out guitar sounds, whereas we don't really bother too much about that,” Carr says.

New Route magazine, September 1992