Like so many artifacts of the 1970s, progressive rock seemed perfectly normal at the time, but in hindsight progrock was pretty much another batshit crazy relic of that era, alongside leisure suits, shag carpeting, and waterbeds. Dave Weigel's "The Show That Never Ends: The Rise and Fall of Prog Rock" does an excellent job of capturing both the madness and the occasional shimmers of brilliance from this curious genre of music.

Progressive rock starts took their mission, and themselves, very, very seriously indeed at the time. The idea of this self-consciously arty form of rock n' roll seemed to be spawned by the Beatles' "Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band" album in 1967, though many pop acts, from The Who to Jan & Dean, had already getting creative with the then still-relatively new ~40-minute long player record format for much of that decade already. Rock n' roll, which was driving Top 40 pop music at the time, was by nature a primitive thing, working best with big beats and inchoate words that conveyed simple, forceful sentiments mostly around love, the loss of love, or a lustful anticipant of love.

Weigel does a brilliant job of striking a balance between offering an earnest, and infectious, adulation of the music, and keeping a critical distance to see the many follies of the genre, making this book smarter, and more enjoyable, than a standard rock history tome. He makes no attempt for an exhaustive chronological history.

Instead, to advance the narrative, Weigel jumps across different groups mixing in the best tales from notable bands of the era, such as England's Soft Machine, Hawkwind, Nice, Caravan, France's Gong as well as Magma (a band so ambitious it created its own language), the Dutch-based Focus, and others. My only pet peeve of the book is that it can jump between groups, and even entire years with little transition, at times, making the book a bumpy ride to follow.

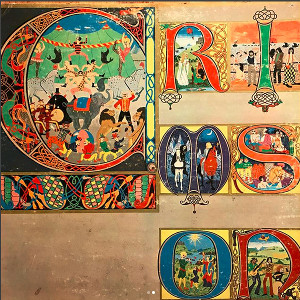

There are a handful of acts given an in-depth retelling, and they are, arguably, the best exemplars of the genre in all its outlandish glories, and they all made their names in the 1970s: King Crimson, Yes, Genesis, and Emerson Lake and Palmer.

While there was no shortage of ego all around in this group, arguably King Crimson founder Robert Fripp made it a high art. "Some would say our music is pretentious. I would say the music is arrogant," he explained to one interviewer. "'Pretentious' means trying to be something you are not. Well, I wonder what we have tried to be that we are not."

Yet, Fripp's Crimson was also arguably the most genuinely innovative of the "art rock" (another term for prog rock used at the time) bands of the day, eschewing the typical proggy classical music pastiche for genuinely groundbreaking music. "You're in a prison and you've got to find your way out of things. I quite like that," said drummer Bill Bruford, of his time with the band. Decades later, edgy hard rock groups like Tool and Nirvana would cite Crimson as an influence.

Though, for all of Fripp's high-mindedness, he was not above enjoying a profitable little side hustle selling used Mellotrons, claiming each one was the very one that gave the group's debut its haunting sound "In the Court of the Crimson King" (I love all the dirt Weigel dishes in this book).

The most pompous, though also the saddest, story, was that of Emerson, Lake and Palmer. A three piece of musical virtuosos, they took the progressive rock mission statement perhaps the most literally, attempting to literally infuse classical music with a rock-like urgent grandiosity. Keyboard virtuoso Keith Emerson conceived of the name for the groups "Works" album from all the classical music box sets that he, then composing in the Caribbean, got his cocaine delivered in.

Today, divorced from the context of its originally mass popularity (ELP shows filled areas in the 1970s), the group's music can have an almost avant-garde feel, with Emerson twisting musique concrete from his long-suffering keyboards. ELP played with an almost surreal bombastic furor, even - especially -when covering classical fare such as "Pictures at an Exhibition."

And from the start of career, Emerson played his keyboards with a fervent aggression. In 1965, Emerson could not understand, while on tour with alongside Manford Mann with his first band, Nice, how Mann's organ was louder than his own each night (Answer: Mann secretly had someone turn Emerson's down). Later, when ELP was first making a name for itself, a roadie (Lemmy Kilmister actually), lent Emerson two German Army knives that he could use to wedge between the Hammond organ keys when playing live so their notes would play, freeing Keith up to go torture another instrument.

Yet, Keith's epic precocity proved, sadly, to be his undoing, if only that such prowess could not be maintained through the decades. During a 1991 ELP reunion tour, Emerson suffered through what turned out to be progressive nerve damage in one of his hands. "Some of the nights on that tour, you could see he was in pain," Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson said. By the final ELP 2010 show, Emerson's virtuosity had shrunk so much as to raise the ire of some YouTube onlookers (compare that show to their debut at Isle of Wright). Emerson took criticisms to heart. In 2016, he committed suicide just before departing to Japan to play a series of shows that he announced would be last. Depression, and perhaps drug use, seemed to play a role in his decision to end his life, and some have speculated his waning talents taunted him as well.

Still, Emerson's feats were honored honorably by British comedian Simon Pegg in a skit in the short-lived British comedy show "Big Train." An imprisoned warrior negotiating for an army to overthrow a kingdom, Pegg's character asks include Keith Emerson, one of the "finest" fighters "in all of Rome," thanks to his ability to fend off aggressors with virulent keyboard runs. But bringing Emerson will come at a cost: "As you can see," Pegg explained, "Keith's fascination with the more elaborate end of prog rock has lumbered him with a vast array of keyboards. I'll need 200 mules for the journey."

"Such a journey is not possible with roadies," one of Pegg's conspirators points out.

"The ELP roadies were sold into slavery in Crete!" Pegg proclaimed.

"I thought it was great," Emerson later said in interview. "I was really quite proud actually. It was almost like they knew me very, very well."

Personally, I attribute the downfall of progressive to the simple fact that you just couldn't dance to it, unlike the disco, hard-rock boogie, or even prog rock-crushing punk for that matter (this would not be a lesson lost on techno decades later).

As a music fan tho, I found some great finds in the book. The 1970s Italian band Premiata Forneria Marconi was a major find for me, as was Steve Wilson's Porcupine Tree two decades later. Heck, thanks to "The Show That Never Ends," I've even gained a grudging appreciation for ELP, a band I couldn't stand to listen to for decades. Now, that's what I call good music writing.